Methodism as part of a universal church faces serious questions about its future. Methodism is not only contending with aggressive secularism, but its decline also suggests a church in danger. The mother-church of Methodism, like ‘the founder of the worldwide Anglican Communion, no longer guarantees a leadership role as the power centers move to Africa and Asia.’ [1] Methodism now faces the loss of its distinctiveness or historical perspective and the erosion of clarity about the purpose of Methodism as envisioned by John Wesley. To overcome the danger Methodism is facing, Methodist Church Nigeria (MCN) corporate episcopacy impacted by usable postcolonial ethic remains faithful to the faith of our fathers with missional potential to decolonize Methodism for our world today.

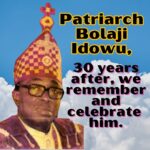

Enugu 2023, which marks 47 years of episcopacy and 40 years of the gathering of the Council of Bishops, MCN, offers us a profound opportunity to celebrate our episcopal epiphany, Patriarch Professor Bolaji Idowu at 110 (1913-1993). [2] The gathering and the celebration suggests a Kairos time of strategizing and reflection on the vision behind MCN Episcopacy as a missional Order[3] envisioned and commissioned to decolonise Methodism for our world today.[4] The missiology and philosophy of MCN Episcopacy as a discipline and practice are transformative, redeeming and renewing (Rom. 12). To decolonise as a verb is a call to transformation and renewal to safeguard the purpose of the Church through the ministry of home and foreign missions. In this context, decolonization is not a metaphor, but missional actions to overcome colonial/Euro-centric narratives and heritages especially racial practices, cultural pride, and superiority. To decolonise Methodism demands restoring Wesleyan DNA to spread scriptural holiness across the world as our parish.

The spread of Methodism to Africa and Nigeria was not just through colonialism but also a missional wave of globalisation. Colonialism is global and historic. Various cultural, financial, and technological elements were attached to the spread of Methodism in Nigeria. The colonial enterprise re-drawn and reshaped our boundaries, political arrangements, and structure and reordered our economic orientation, ancient institutions, and landmarks. Beyond its religious and cultural impacts on the African landscape, the missionary enterprise ‘tinkered with its dominant worldview and value system.’ The colonial missionary worldview shaped by their cultural baggage and Euro-centric perceptions impacted our principle of morality and spirituality.

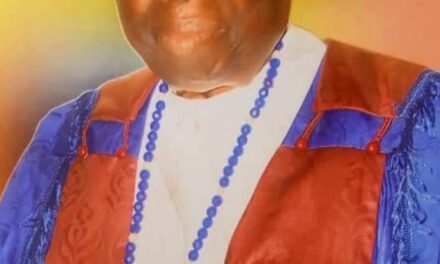

Patriarch Idowu, the foremost MCN’s academic remains Nigeria’s great gift to the world church, academics, and Methodism. [5] Patriarch Idowu explained that the European missionary came to Africa with the preconceived notion that there was either no religion at all in Africa or that it was entirely of the Devil. [6] Patriarch Idowu pioneered a “radical indigenisation of the Church” as a starting point to remedy the predicament of dependence resulting from Western cultural dominance and pride. The colonial missionary failed to see and learn from the pre-modern Christian religious traditions, undermining the African God-given heritage of indigenous spiritual and cultural treasures. [7] God’s mission, which was supposed to be a mutual partnership, became a one-directional process initiated and dictated by one dominant group. Indeed, he who paid the piper called the tune.

Sir Familusi, in his assessment of Patriarch Idowu and his service to the Methodist Church Nigeria (MCN), said, “There is no doubt, however, that His Pre-Eminence Bolaji will remain the first Patriarch of Nigeria Methodist Church–notwithstanding whatever happens after him to that very honorable and highly time-honoured, worldwide revered title, Patriarch, His Pre-Eminence has done much more than any of His predecessors to lift the Methodist Church Nigeria to Pre-Eminence. He had an unprecedented foresight and planned to meet and affect his imagination of things to come. God’s work prospered in his hands–the number of dioceses rising from seven to fifteen and that of the ordained ministers from about a hundred to over three hundred during his time. The Christ Zion Methodist Church Nigeria, Incorporated fused with MCN before he left office. The new order of deaconesses and the improved liturgy and order of worship will remain a permanent tribute to His Pre-Eminence Bolaji.” [8] Patriarch Idowu’s ingenuity and courage gave MCN a ‘new identity, the pride of selfhood and dignity of autonomy, and autocephaly.’ MCN’s Episcopacy missional identity with spread to many African countries is to decolonised Methodism for mutual partnership in global mission.

Thirty years after his transition, we know how far we are from reaching Patriarch Idowu’s envisioned goal for MCN and our Episcopacy, especially in missional response to colonisation and globalisation. Familusi described Patriarch Idowu as a colossus and dreamer par excellence like Joseph, hated by his brothers. Just as the dreamer lives forever, Patriarch lives on with great cathedrals and magnificent edifices of worship and as an architect who had a vision of a temple of worship and put the vision upon paper. Patriarch Idowu was a great dreamer in the realm of theology, liturgy, and churchmanship with ‘a vision of a Church needing liberation and emancipation for true African selfhood.’ At 110, Patriarch Idowu’s handworks have continued to shine in world circles. His native intelligence and academic prowess have continued to enlighten and challenging the universe. His initiative has drastically transformed the MCN and World Methodism.

Patriarch Idowu’s envisioned goals point to the MCN’s Episcopacy as one of the world’s best-equipped missional and corporate Episcopal Orders to decolonise and spread Methodism worldwide. MCN’s Episcopacy as indigenised missional leadership means of grace for effective church life, partnership, and ministry is shaped to decolonise Methodism to spread scriptural holiness.[9] The authority of the MCN’s Episcopacy comes from Christ in (His Church) the Conference and purposely to safeguard the Church against erroneous teaching and practices.[10] MCN’s Episcopacy beyond the context of post-autonomous colonial Methodist jurisdiction, reshaping and reordering values the gifts of apostolicity and catholicity commission through historic ministry and matters. MCN’s Episcopacy as a historical and corporate episcopate also ‘stands for, and admits to, the controlling partnership of truth and holiness between all Christian generations, which is our common heritage.’ [11]

Episcopacy, which has become autocracy or ceremonial, remains a caricature. MCN’s Episcopacy as a counter-cultural is open to entering mission partnerships with others.

MCN, in continuation of its repositioning agenda coupled with the challenges of globalisation needs a new look, especially in the global context. Leadership development in MCN traced into four periods has experienced about five cycles of presidential and episcopal constitutions between 1962 to 2006. [12] The 1962 autonomy constitution with Rev. Soremekun as the first autonomous President did not change the original structure of the church leadership inherited from the British Conference. [13] The election and designation of Rev Professor Bolaji Idowu as President on October 4, 1972, led to a corporate episcopal reordering of the life and leadership of Nigerian Methodism based on the 1974 Asaba Retreat. In 1974 at the 13th annual Conference of Methodist Church Nigeria held at Immanuel College, Ibadan, Justice Olu Ayoola, the chairman of the Constitution Drafting Committee, introduced a new constitution with the traditional ecclesiastical title of Deacons, Priests, Presbyters, Bishops, Archbishop and Patriarch. [14] In 1975, at the Calabar Conference, the new Constitution was passed, and the President, Rev Professor Idowu, was unanimously elected the Patriarch.[15] On January 20, 1976, generally referred to as The Appointed Day, Patriarch, Archbishops, and Bishops were invested and consecrated. [16]

Very Rev Professor Segun Ilesanmi aptly described Patriarch Idowu as someone ‘shaped by dual professional identity.’ As a clergyman, Professor Idowu called more intently at African Christianity (Methodism) ‘to embrace indigenous religious sensitivity as a prerequisite to their survival in Africa’ and worldwide. Indigenisation as a cultural and intellectual project[17] “was part of a much broader movement aimed at fostering black self-respect, a goal which, apart from theology, required a complete reorientation in areas such as historiography and, not to forget, literature.” [18] Patriarch Idowu’s mature mind as a religious scholar was better expressed in his Inaugural Lecture in 1974 at the University of Ibadan titled, Obituary: God’s or Man’s? [19] The lecture still speaks to us today just as ‘that at the time reveals more about the cultural concerns of the Western world than the prevailing ideological mood in Africa.’

Indeed, Patriarch Idowu ‘chose the podium afforded by the aura of inaugural lectures to address this problem not just stylistic but definitional, in that he wanted to speak as a public intellectual on an issue that straddles his two professional guilds – the university community and a religious body – which are the traditional avenues from which society expects intellectual and moral guidance on the issue of public importance.’ As a public intellectual and theologian, Patriarch Idowu typically “seek to unite – in their thinking, speaking, and writing – the tasks and virtues of scholarship with the tasks and virtues of citizenship. As a public intellectual and theologian, Patriarch Idowu ‘seeks to balance the scholar’s critical distance from taken-for-granted assumptions and institutions with the citizen’s commitment to a shared moral life.’ [20] Patriarch Idowu educated the Church through his long Patriarch’s addresses to Conference, original, down-to-earth, educational, inspiring, and challenging. Among the titles of his speeches were: On His Divine Majesty’s Service, The Keys to the Kingdom, and The Church of Believers. He founded a tailoring factory for the Church. [21]

According to Ilesanmi, Professor Idowu’s ‘goal was to offer conceptual and analytical tools by which to understand a particular problem but also to explain why an awareness of paradox and ambiguity should not become an excuse for moral (church/mission) paralysis and, thus why religious people, especially Christians, should try to change a world that was so resistant to their efforts and so difficult to understand.’ Patriarch Idowu’s conceptual and analytical tools shaped MCN’s Episcopacy based on Asaba Retreat to indigenised and decolonise MCN. Sadly, in response to the crisis in MCN, the Ministerial session of the Conference at Otukpo in 1984[22] retired Patriarch Idowu and his chaplain, Rt. Rev. Sunday Mbang was elected to succeed him. [23]

MCN, shaped by Wesleyan spiritual history, remains mission-oriented with a leadership strategy for mission across the world as our parish through the bishops as the real theologians of their various dioceses and mission areas. In two of his books, Towards an Indigenous Church and The Selfhood of the Church, Patriarch Idowu projected MCN’s Episcopacy through a missional lens. The doctrine and nature of MCN’s Episcopacy are to obey the Great Commission as ‘a powerful living stream which flows into and through the nations, giving of itself to enrich the people and transforming the land, bringing from and depositing in each place something of the chemical wealth of the soils which it encounters on its way, at the same time adapting itself to the shape and features of each locality, taking its colouring from the native soil, while despite all these structural adaptations and diversifications it esse and differentia are not imperilled but maintained in consequence of the living, ever replenishing, ever revitalising spring, which is its source.’ [24]

MCN’s Episcopacy is applied leadership theology shaped by ‘the burden of giving the Church in Nigeria an indigenous complexion … rest heavily upon Christian Nigerians. No foreigner can do the work for them.’ According to Patriarch Idowu, MCN’s Episcopacy suggests an expression ‘that the church ought to come of age in Africa and in Nigeria and discarded prefabricated European dominated liturgist and structures.’ The counter-cultural nature of MCN’s Episcopacy resonates with the Wesleyan DNA, including ‘a profound rejection of cultural and nominal Christianity and a call to radical commitment to an alternative lifestyle in the service of God who made the ultimate sacrifice for the good of humanity.’ MCN’s Episcopacy, in its appeal to Primitive Christianity, enhances a matter of polity into a dynamic tool for mission and leadership.

Missiologists continue to alert us to the impact of colonisation, urbanisation, and globalisation on the Church and society in general. Mission demography continues to change just as urban population occurs across national and global boundaries. Professor Andrew Walls compared the early story of attempted globalization with the punitive construction of the Tower of Babel and the long saga of Abraham (Gen 11:5-9, 12:104). [25] Methodism, as a significant part of the pre-WWI wave of globalisation was not just colonialism. The Christendom and colonial violent politics, aggressive and self-centred economics, mission jurisdiction, and fierce militarism affected the spread of Methodism. [26] Mission work in the past was alongside imperialism. The spread of Methodism as a wave of globalisation in the late 19th and 20th century was through ‘various technological, financial, social, and cultural elements.’ [27] The increased wave of nationalism made MCN’s Episcopacy flourish just as the pandemic recovery unleashed a new wave of mission globalisation and a decline in colonised denominations.

A global renewal and return to the spiritual foundation of Methodism is not possible without decolonising the Christendom heritage of self-serving mission ethics shaped by social and military compulsions in the cause of its mission efforts. Methodist connexion as migratory network points to the world as a mission field with a world vision and mission.[28] MCN’s Episcopacy as an indigenised co-mission with God, a means of missional leadership to decolonised Methodism is a global commission envisioned by Patriarch Idowu’s liberation and emancipation for true church selfhood. Today, there is massive movements of Nigerian Methodists from rural to urban areas and between countries. [29] The massive movement is also fuelled by ‘globalisation, a phenomenon marked by increased speed of travel, communication, and trade in a highly technological age.’ [30] MCN’s Episcopacy speaks of God’s mission through the incarnation of Christ in a world under the yoke of sin divisions. MCN’s Episcopacy as a global missional reality of a dreamer, Patriarch Idowu remains an episcopal architect and mission catalyst envisioned to be counter-cultural globally.

MCN’s Episcopacy in a globalised world needs to understand the differences between the colonised world of the missionary and globalised mission in today’s world. The understanding calls for different units of episcopal commissions for renewal, guarding the Methodist faith, unity, discipline, and of the Church in general. [31] These commissions comprising of the episcopal and theologians (Lay and clergy), including professionals, are to promote God’s mission by organising, and facilitating periodic updating seminars, training, development, and dialogues.

To decolonise Methodism worldwide, MCN, as the first Christian denomination in Nigeria, must be at the forefront, making a case for renewal, justice, and bold witness of the Christian faith. Our population and numbers of our Bishops are not just our strength; hence the varieties of God’s gift within us summon us to be in Co-mission with God, for example, Episcopal Commissions on – Dioceses, Catechesis, and Methodism; Security, Ecumenical Affairs, and Inter-religious Dialogue; Family life, Sport and Recreation; Health and Social Care, Agriculture, and Community renewal; Liturgy, Mission, and Evangelism; Politics, Judiciary, and Public Orientation; Theological Education and Digital Communication; Social Action, Poverty alleviation, Justice and Peace; Finance, Economy, Power, and Mineral resources among others.

At a time when the progressive theological views are becoming regressive under the weight of colonised, long-term dysfunctional, and disparate modern theologies, it is a season of discernment for the Nigerian Methodist Episcopal Commissions to reclaim the theological roots and practices to fuel global renewal.

[1] Turnbull, Michael, McFadyen, Donald, The State of the Church, and the Church of the State (London: DLT, 2012), p. 5

[2] Awolalu, J. Omosade, ‘A Leader and a Mentor: Memorable Thoughts in Honour of Prof. E. Bolaji Idowu’ in Abogunrin, S. Oyin, Ayegboyin, I. Deji (eds), Under the Shelter of Olodumare, Essays in Memory of Professor E. Bolaji Idowu (Ibadan: John Archers, 2014), pp. 1-4.

[3] Okegbile, Deji, Missional Leadership for Repositioning Nigerian Methodism (Lagos: Alet Inspiratioz, 2019), pp. 3-13

[4] Methodist Church Nigeria: The Asaba Retreat Document, February 1-3, 1974, Matters Relating to the Life of the Church and Faith and Order, p. 13

[5] Archbishop Ebere O Nze, ‘Encouraging the Heart,’ in NOW, Methodist Church Overseas Division, London, February 1988, p. 9

[6] Idowu, Bolaji, The Predicament of the Church in Africa,’ Christianity in Tropical Africa,1968, pp 415-440 in Kwame Bediako: ‘Understanding African Theology in the 20th century’, October 1 9 9 4, pp. 15-16

[7] Idowu, Bolaji, Towards an Indigenous Church (London: Oxford, 1965), pp. 26, 6

[8] Familusi’s Tribute during the 10th anniversary of Patriarch Bolaji Idowu service in 2003.

[9] http://dejiokegbile.com/methodism-nigeria-premier-church-180-and-autonomy-60-indigenised-to-decolonise-8/

[10] Olegario Gonzales de Cardedal, ‘Episcopacy Root and Branch,’ in Moore, Peter (ed), Bishops: But What Kind? Reflections on Episcopacy (London: SPCK, 1982), pp. 51-67 [11] Conversations between the Church of England and the Methodist Church: A Report to the Archbishop and York and the Conference of the Methodist Church, Church Information Office, and The Epworth Press, 1963, pp. 24-27.

[12] Okegbile, Missional Leadership, pp, 5-13

[13] The Methodist Church Nigeria: Constitution and Standing Orders with Deed of Foundation and Deed of Church Order, 1962

[14] Methodist Church Nigeria, Constitution (Lagos: Methodist Church, 1976), pp. 4-9.

[15] Okegbile, Missional Leadership, p. 8

[16] Methodist Church Nigeria: ‘The Appointed Day Services’ – Ratification of the New Constitution, January 20 1976; Commemorative Service No. 2: Consecration and Investiture of Archbishops and Bishops, January 21, 1976 and others (1-6), Lagos.

[17] Idowu,, Towards An Indigenous Church, pp. 5-9

[18] Schoffeleers, Matthew cited in Ilesanmi, Simeon, The Gods Are Not to Blame: An Examination of E. Bolaji Idowu’s Perspective on the Paradox of Religion in Nigeria in Abogunrin, Oyin, S. and Ayegboyin, Deji, I. Under the Shelter of Olodumare: Essays in Memory of Professor E. Bolaji Idowu (Ibadan: John Archers, 2014), pp. 340-341

[19] Idowu, E. Bolaji, Obituary: God’s or Man’s? An Inaugural Lecture delivered at the University of Ibadan on Thursday, October 24, 1974 (Ibadan: University of Ibadan Press, 1974).

[20] Grelle, Brice cited in Ilesanmi, The Gods Are Not to Blame, p341

[21] Methodist Church of Nigeria, “His Pre-Eminence Bolaji 1913-1993” Brochure for the 10thYear Remembrance Service (Patriarch Bolaji Methodist Cathedral, Ita-Elewa, Ikorodu, Thursday, November 27, 2003) 1-2; 15-16.

[22] Okegbile, Deji, Evangelism in the New Millennium: A Call to Methodist Re-Awakening (Kaduna, Poskem Venture, 1999), pp. 22-24.

[23] Okegbile, Missional Leadership, p. 8

[24]http://dejiokegbile.com/bolaji-idowu-lives-on-methodist-episcopacy-at-40/

[25] Gornik, Mark R. (ed), Walls, Andrew F., Crossing Cultural Frontiers: Studies in the History of World Christianity (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2017), p. 53.

[26] https://docplayer.net/53748783-Europe-christendom-graveyard-or-christian-laboratory.html

[27] https://um-insight.net/in-the-church/umc-global-nature/worldwide-methodism-amid-waning-globalization/

[28] Davie, Martin, Bishops Past, Present and Future (Great Britain: Gilead Books, 2022), pp. 200- 291, 721-784.

[29] Forster, Dion, Decolonising Methodism around the world, in Methodist Recorder, Issue 8556, December 17, 2021, bp.

[30] Wu, Siu Fung, Reading Romans in a Globalized and Increasingly Urban World,’ in Mission Studies, Journal of the International Association for Mission Studies, Volume 35, No 3, 2018, pp. 322-324.

[31] Episcopal Ministry: The Report of the Archbishop’s Group on the Episcopate, 1990, Church House Publishing, London, pp. vii-ix, 319, 173-232.

Recent Comments