Episcopacy is not an end in itself. It is a means to the one supreme aim: Spreading the scriptural holiness throughout the land – Bishop T. T. Solaru.

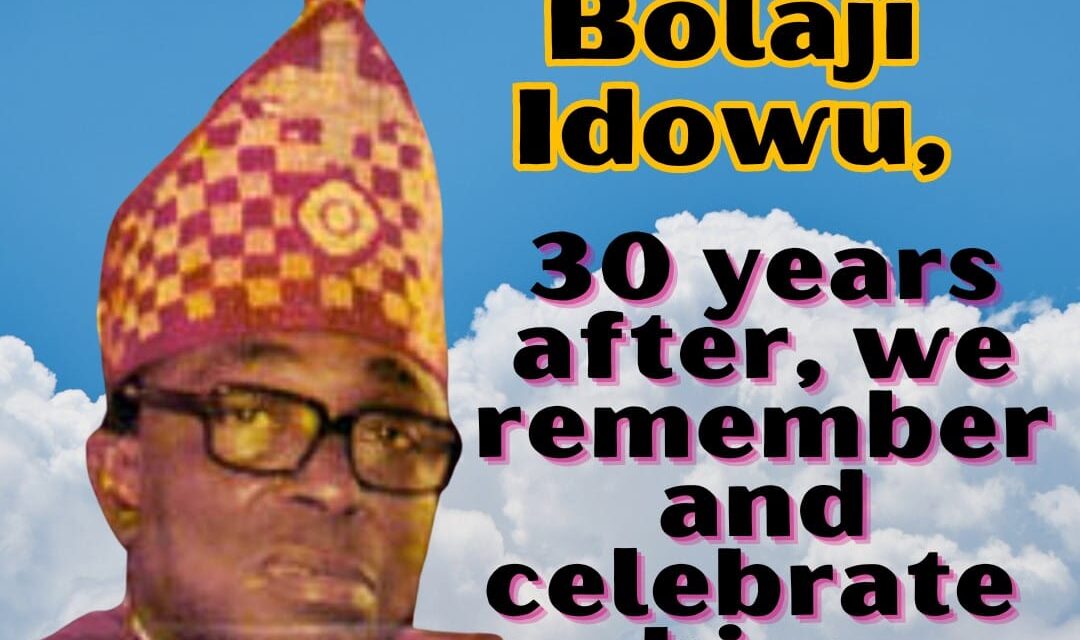

Loving memories never die. Patriarch Professor Emmanuel Bolaji Idowu was born on September 28, 1913, changed mortality for immortality on November 27, 1993, and was buried on December 17, 1993, at Ikorodu. Patriarch Idowu, the third and last President of Methodist Church Nigeria, was the first Nigerian Head of the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Ibadan. According to Professor Omosade Awolalu, Patriarch Idowu’ brought remarkable changes to the academic study of Religions in the Department.’ Patriarch Idowu, who joined the University’s academic staff and was promoted to the rank of professor in 1963, was also the first African chairman of the Chapel of Resurrection, University of Ibadan.

Patriarch Idowu was elected President of Methodist Church Nigeria on October 4, 1972, at Methodist Church, Yaba, Lagos. In 1973, Patriarch Idowu called for reviewing the church’s Constitution as an autonomous church in Nigeria. The task also includes ordering the life of the church for effectiveness in the peoples’ native context, and this calls for an urgent process of the church’s indigenisation. A historic assembly for all Methodist Churches in Nigeria was held at Asaba from February 1-3, 1974, to set up the new pattern for Nigerian Methodism. At the 13th Conference of Methodist Church Nigeria held in Immanuel College Chapel, Ibadan, from November 27 to December 5, 1974, the Constitution Drafting Committee of Methodist eminent lawyers and members of the Faith and Order Committee headed by Hon Justice Olu Ayoola introduced the proposed Constitution. After amendments were made, the Conference approved the new Constitution. A special committee was set up to read through the draft before the 14th annual Conference at Calabar from September 2 to 12, 1975, ratified the final copy and fixed January 20, 1976, as the “Appointed Day” service at Methodist Church of the Trinity, Tinubu, Lagos. The service began an indigenous corporate Methodist episcopacy in Nigeria where Patriarch Idowu and other appointed Archbishop and Bishops were consecrated and invested.

Indeed, Patriarch Idowu remains synonymous with Nigerian Methodist episcopacy and the Department of Religious Studies, University of Ibadan. Celebrating Patriarch Idowu’s 110 post-humous birthday and 30 years after his transition, it is essential to reflect on how Patriarch Idowu, as the first Patriarch of Methodist Church Nigeria (1976-1984), led the church in creating the New Constitution (1976) and inaugurating the patriarchy and adopting Methodist corporate Episcopacy. The New Constitution was not just a purely democratic setup. Bishop T. T. Solaru, the first Methodist bishop of Ibadan, in his sermon, preached at the Service of Thanksgiving in connection with “The Appointed Day events at Hoarse’s Memorial Methodist Church, Yaba on January 26, 1976, said, “Episcopacy is not an end itself. It is a means to the supreme aim: Spreading the scriptural holiness throughout the land.” According to Bishop Solaru, the successful execution of one part of the ASABA retreat proposals, the Methodist 1976 Constitution, must be followed with the enriching and renewing concept of Methodist Liturgy, Ritual and Offices. The follow-up would help the church regain, retain, and increase the living experience of Jesus Christ. Bishop Solaru said, ‘Only this will open our eyes and strengthen our desires to do God’s will. It is our duty to give a sense of direction to the lost in our nation.’ Patriarch Idowu’s episcopal theology and philosophy is an authentic relational leadership, where the lamps of good fellowship are always kept burning, the unity of the mission is never compromised, trust is never betrayed, and the mission is cheerfully and sacrificially pursued.

The 1976 Methodist Constitution was not without a natural consequence of the process of coming into being. The doubts, suspicions, acrimonies, and even bitterness engendered through the exercise of producing the Constitution distracted the church and led to over 14 years of crisis. In 1984 at Otukpo Methodist Conference, Patriarch Idowu’s chaplain, His Eminence Dr Sunday Mbang was elected as the new Patriarch. Patriarch Idowu retired at age 71 on September 28, 1984, after 12 years as the head of Methodist Church Nigeria.

In his Patriarch’s Address to the 17th Annual Conference, Methodist Church Nigeria held at the Enugu Campus of the University of Nigeria, August 23 to September 1, 1978, Patriarch Idowu emphasised the theme of the 1978 Conference, ‘On His Divine Majesty’s Service’ as a development since 1973. Patriarch Idowu explained that the theme was designed to call the leadership to a sense of urgency to our commitment as a church, to give the church leadership a keen awareness that we cannot, or can no longer, afford to trifle with the commission laid upon the church by a Holy God if we are not to cease to be a church and be reduced to a mere form of incompetent contractors “in a kingdom of God industry.” Episcopacy, reduced to a mere firm of incompetent contractors, warns against the overwhelming responsibilities of corporate management with endless meetings and replies to an avalanche of letters. Episcopacy beyond the cosmetic or career of a caregiver points to actions that counter lack of integrity and trust, which does not allow for the fulfilment of episcopal vows.

Patriarch Idowu used the 1978 Methodist Conference key-note prayer, “May our service to the future pay our debt to the past,” to remind the church sent to the end that we may be equipped with the spirit of discernment to appreciate the fact that others have laboured, and we have entered their labour. Therefore, we are expected to leave behind a heritage of noble responses in fulfilled assignments and missions for the coming generations. The 1978 Methodist Conference theme, according to Patriarch Idowu, with his reference to the spiritual and moral signs of the country 45 years ago, called for an urgent need to pause and think, examine us, and, under God, set things to right where they have gone wrong or where they are going wrong.

The situation is worse today in the church and our national politics. Using the words of Patriarch Idowu, a sense of our calling, of the task set before us by the Lord of the Church should ‘make us rise from the table of folly, avoid and put away all filthiness and rank growth of wickedness – every dead weight which is hampering our movements and every obstacle in the way of our spiritual progress.’ The good news is that Methodist Church Nigeria is an organism, evolving a new life for renewal and revival.

Remembering the genius of Patriarch Idowu 30 years after his transition, he warns the church against Episcopacy becoming ‘ecclesiastical cosmetic.’ He explained that the 1976 Methodist Constitution is ‘not an ecclesiastical cosmetic to serve the vanity of a church; it is the Lord’s renewed call to us that we so live and conduct ourselves that the Church, with us as servants and instruments, shall be found relevant to the needs of modern age and generation with all their demands and challenges.’ Patriarch Idowu found ‘ecclesiastic cosmetic’ alive and well in the church. It appears to be busy but guilty, lacks humility, lacks a servant’s heart, and is selfish and infatuated with title, position, ego, power, and popularity. Methodist Episcopacy beyond ecclesiastical cosmetics counters an elaborate window dressing and papering over the church leadership’s cracks. Ecclesiastical cosmetics are applied on the surface and superficial. It needs more depth.

Beyond celebrating leaders and personalities as human penchant, Patriarch Idowu’s name and symbolic legacies remind us of the Church, according to Scripture and ecclesiastical tradition and recognition of persons who have responded to the divine calling and election, separated by ordination and consecration for service. Patriarch Idowu says such persons are uniquely the “Lord’s anointed” by their position. They are members of the Body of Christ and not just into ecclesiastical cosmetics when the civic leadership devolved into the hands of bishops grants them a new kind of power, a new degree of influence, over the governance and organization of their domains. Episcopal ecclesiastical cosmetic brings to the fore the social leadership for example exercised by Gallic bishops, which resonates today with the pursuit of self-serving to seek control over others and essential places. Patriarch Idowu’s episcopal ideology described him as a lover of the poor, shaped by his devotion to God.

Episcopacy dressed in ecclesiastical cosmetics reminds us how the episcopal throne promotes the acquisition of wealth and the quest for honour. History of the wealth and power of the Episcopacy in the sixth century reminds us how successful secular careers attracted the grandfather of Gregory of Tours. The bishop’s throne became the natural culmination of a successful aristocratic cursus honorum. In essence, the bishop of a large See became a great officer of State. The cathedral became very attractive, especially in the fifth century, just as the church became a political power base to counter the influence of Italy and the imperial centre, a clue to the emergence of the ‘episcopat monarchique.’ The secularisation of episcopacy remains a dangerous development but the misleading experience should not now prejudice a more wholesome appreciation of the possibilities of episcopacy as a means of spreading scriptural holiness across the land.

Patriarch Idowu was not unaware of the development and challenges of the dynasticism of the Episcopacy from the second century until the fourth in the control of the religious and political life of their communities. Patriarch Idowu’s ideology of episcopacy counters means of granting a veneer of spiritual validation to ecclesiastical cosmetics and colonisation. Patriarch Idowu reinforced the existing social and indigenous conditions, emphasising the transience of this world and life and the importance of life to come. Episcopacy shaped by ecclesiastic cosmetics and career is rooted in leadership without vision but only for the glory, fame, control, popularity, and power that leadership positions have to offer them, and do not have a sense of fulfilling the Great Commission. Episcopacy through the lens of ecclesiastical cosmetics looks beautiful on the outside; it is glamorous; it is expensive, but within is emptiness, lacks integrity and cannot be trusted (Matt 23:1-7). Patriarch Idowu’s vision of Episcopacy provides a renewing and redeeming reference for the church and political leadership. The church and the nation need a pastoral, caring episcopate, which it has had and still possesses in many individuals like Patriarch Idowu. He lives on.

Thanks for the piece. God bless you my dearest brother and bishop

Worthy is the Lamb!