St Augustine aptly describe a hymn as, “a song with praise of God,” and ‘to praise God is the high calling of man.’ What the hymns of Charles Wesley are to the Wesleyan Methodism inspires and resonates with the spirituality of Ikoli Harcourt Whyte’s hymns to Primitive Methodism in Nigeria. The Rev. Dr Lord Leslie Griffiths, the former Superintendent Minister of Wesley’s Chapel, London in one of his writings, Charles Wesley: A Treasury of Theology in Song, provides us some important clue to hymns of the Evangelical Revival during the great Whitsuntide of 1738 and its expansion to other nations, like Nigeria. According to Griffiths, ‘And these great hymns were written to feed the faith, steel the nerve, and fire the soul of those who made common cause with the people called Methodists.’ To celebrate the 230 years death anniversary of the Methodist main characteristic poet, Charles Wesley, the name of the Nigerian man, Ikoli Harcourt Whyte who composed some hundreds of native hymns on some ‘subject within the compass of Christianity, despite having leprosy comes to remembrance.

Methodism was born in song filled and inspired by every part of the New Testament. Remembering Wesley and Whyte points to two catalysts of Evangelical hymns and faith that always sing its creed. In the words of Griffiths, ‘Methodists have always sung their theology. Charles Wesley was the absolute master of taking the teachings of the Bible and an understanding of abstruse theological concepts and, by skilful weaving and with a sure feel for words, turning his material into accessible, memorable, uplifting verse. It was pure genius.’ Wesley’s and Whyte’s ‘hymns appeal to young and old alike and because it is well that the young should learn the range of the Christian life.’ Wesley and Whyte hymns are not only applicable ‘for select gatherings or for solitary communion with God, they are suitable ‘either in public or private worship,’ they echoes the joy of our salvation only in Jesus Christ. Song as the people’s part, especially in Methodism, Wesley’s and Whyte’s hymns inspires and calls the whole congregation to sing the hymns. Through Wesley’s and Whyte’s hymns, ‘men speak to the Most High and He to them.’

Charles Wesley was born on 18th December 1707 in the Rectory, Epworth in Lincolnshire. He was the 18th child and youngest son of the Revd Samuel and Mrs Susannah Wesley. He died on March 29, 1788 in Marylebone, London and on his deathbed, he wrote:

In age and feebleness extreme,

Who shall a helpless worm redeem?

Jesus, my only hope Thou art,

Strength of my failing flesh and heart,:

O, could I catch a smile from Thee

And drop into eternity!

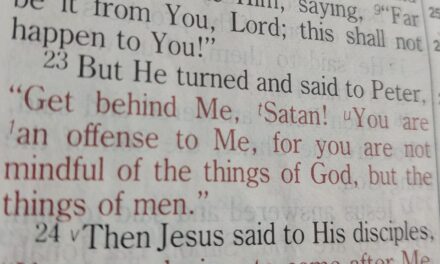

The celebration of the 230 years anniversary of Charles Wesley’s death on a Maundy Thursday summons us to receive Jesus Christ as the only hope to redeem our helpless worm and thereby aspire to ‘catch a smile … And drop into eternity.’ With over 6, 500 texts, ‘Charles Wesley wrote for the streets [of his time], for down-at-heel people, for the unlearned, for a church on the move. He democratised church music, released it from the hands of the super-skilled and gave it to ordinary people.’

Whyte, the Nigeria’s most famous victim of leprosy, born in 1905, ‘was diagnosed with leprosy as a teenager, at a time when there was no effective cure for the dreaded disease which usually leads to deformity of the hands and feet.’ Accordig to Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani, ‘people suffering from leprosy were often isolated or driven away from their communities. Whyte channelled his experience of suffering and stigmatisation into music, and went on to compose more than 200 inspirational hymns.’ Nwaubani, citing Achinivu Kanu Achinivu, a professor of music who was a friend and protégé of Whyte explained that Whyte, “…wrote very slowly. It took him a whole day or more to write one page of music.” Whyte was ‘born in Abonnema, Rivers State of Nigeria and diagnosed with leprosy in 1919. He was ‘inmate at the Uzuakoli Leprosy Colony in south-eastern Nigeria from 1932, despite being cured in 1945. Composed over 200 hymns, mostly in the Igbo language. Set up a choir made up of people living with leprosy, who toured Nigeria. His choir sang for British dignitaries who visited colonial Nigeria. Included Ikoli (a traditional name) in his birth name, so as to not be mistaken for a foreigner.’ Whyte taught music at Methodist Boys’ High School, Uzuakoli where he met Professor Achinivu in the early 1950s.

Since the death of Whyte in a motor accident in 1977 after a fatal motor accident, his ‘talent for music was developed at the Uzuakoli Leprosy Centre in what is now Abia State in south-eastern Nigeria, where he spent the last 45 years of his life.’ Methodist missionaries intervened based on Whyte’s and others persistent activism in support of people with leprosy. Methodist missionaries later ‘established the Uzuakoli Leprosy Centre in 1932, with Whyte and his fellow patients as some of the first set of inmates.’ At Uzuakoli, Whyte met his helper of destiny, a British missionary and medical doctor, Thomas Frank Davey, a music lover and a pianist – an association that became the catalyst for his music career. Whyte remain and formed a choir made up of other patients at the Uzuakoli centre after he was declared cure of leprosy in 1949.

In remembering and celebrating 230 years death anniversary of Charles Wesley and the inspiration of his hymns to Ikoli Whyte in Nigeria, it important to note that their hymns not only provides solace, comfort and advice, their hymns inspires and awakens our hope in God and the anticipation of the Second Coming of Jesus Christ. While Charles Wesley who suffered from nervous exhaustion and severe depression travelled, preached, wrote poetry and hymns, saw to the work of the Methodist societies, bands, and classes, Ikoli Whyte who suffered from leprosy composed hymns in native Igbo language and saw to the stop of discrimination against people with leprosy. Wesley’s and Whyte’s styles invites us to respond to the gospel of God’s love in Jesus Christ. They summons us to live out our discipleship in worship and mission just as they took the word of God through their activism and hymns to people, wherever they were, rather than try to get them into a church to hear it.

Recent Comments