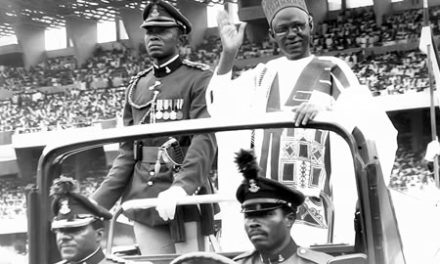

Church mission history reminds us that Constantine’s conversion to Christianity in 312 AD ‘wed the church with the state and set the framework for later colonialism.’ The acts of Constantine and their effects on Christianity reminds us that politicians are not religious representatives. Colonialism understood as western or colonial political expansion,[1] has to a certain degree been eradicated through political independences granted to come nations under colonial political control. Some African countries have seen the end of their status as colonies only in recent years – Zimbabwe in 1980, Namibia in 1990. Sadly, colonialism as expressed in economic, social, and ‘Christian cultural hegemony has only increased.’[2] Nigerian Methodism at 180, indigenised to decolonise generates some questions that need answer: Have we forgotten the missiological heritage and lessons of our past? How do we indigenise by contextualizing or do we continue neocolonializing and redefining faith?

Nigeria Methodism at 180, indigenised to decolonise provides us a missional and cultural expression of Christianity[3] and ‘Christian missions unadulterated by a theology influenced with a political agenda and of an effective missional ecclesiology that was contextual and indigenous.’ All the signs of postmodernity, globalisation, neo-colonialism[4] are seemingly present in contemporary missions: the ideas of colonial cultural superiority, colonial ecclesiastic structures and polity, colonial mission, theology, and ministry methodology. Nigeria Methodism at 180, indigenised to decolonise is a timely missional invitation, forward to the past ‘to revisit or possibly rediscover those lessons from our not so distant past’ in order to overcome our present decline.

Indigenised to decolonise is a missional cry against colonial Christian cultural pride and superiority: cultural, theological, ecclesiastical and historical. Colonization, blatantly as racist, made missionary work to become a duty to conquer the land to civilise the “savage” nations. The presumed “saviours” subjugated the indigenous populations ‘and rejected their deeply rooted beliefs as primitive without bothering to understand Indigenous culture.’ The colonial concept “to missionize is to colonize and to colonize is to missionize.”

Christian mission and colonialism have been inextricably related noting that, ‘the forms of both colonialism and mission have changed over the centuries, they have continued their alliance.’ This alliance points to the problem of neo-colonialism, a new slavery and exploitation of human and natural resources of developing nations. For example, Africa is going through the second scrambling – neo-colonisation. This is even worse than colonisation when Africa was demarcated and partitioned ‘in line with their colonial needs leaving Africans with a destabilised administrative structure, a maladministration which we have inherited till this day.’ Colonization not only sacrilegiously deformed and divided cultures, it also prepared the ground for neo-colonisation, that is, their second coming. Why is the incessant search of the locations of goldmines, oil, and other natural resources in the developing countries by their colonial lords. Are civil wars – religious, political and ethnic uprisings, Boko Haram among others, proxy wars to cause divisions, poverty, oil bunkering and theft, hatred, fears, destabilisation, and thereby disenfranchises developing nations like Mali, Niger, Senegal, Nigeria, and Central African Republic? Neo-colonisation points to a systemic creation of ‘a wide scale conflicts … piquing the North against the South, the Christians against the Muslims, some tribes against the others all in the name of politics and religion.’ Neo-colonisation shapes the ‘shipment of all sorts of sophisticated weapons into the Sahel and Savannah regions.’ Neo-colonisation is an indirect exploitations of the gifts, wealth and human resource of the developing nations.

Beyond overcoming the ventures of colonial Christianity and its legacies, Nigeria Methodism at 180, indigenised to decolonise seek to explain what the basic problems and spirit behind colonial Christianity in order to stop and not return to business as usual – “missionize is to colonise.” Partnership with other Christians with marks of both internal and external colonialism and neo-colonialism calls for urgent change for effective evangelism and mission. Nigeria Methodism at 180, indigenised to decolonise suggests an indigenous theology and mission with potentials ‘to deal with colonialism, neo-colonialism, and postcolonialism.’[5]

Since the 16th century when mission was equated with colonialism, missionaries became pioneers of western colonial expansion,[6] mission societies had a dual mandate, one to evangelise and one to civilize. Nigeria Methodism at 180, indigenised to decolonise asserts that becoming a Christian is not about becoming civilise bearing in mind that, traditional cultural forms for indigenous belief is not inferior to the western Christian civilisation. Indigenised to decolonise is a theological force against colonialism. While the focus of colonialism was bringing the nations to Jesus Christ through civilization, indigenised to decolonise is about bringing Jesus Christ to the nations through evangelism shaped by ‘a premillennial view of Christ’s return.’ The present church decline and moral depravity equal Sodom and Gomorrah today points to the ‘growing recognition that the world’ is not becoming more civilized but cruel and crumbling.

Two main roadblocks to effective mission partnership around the world today include the fact that ‘failure to consider our colonial heritage may result in failure to understand who we are today.’ Nigeria Methodism at 180, indigenised to decolonise answers ‘how we have been shaped by our histories.’ Secondly, the ‘failure to deal with our colonial histories may also result in failure to deal with the neo-colonial histories that are now being made and thus in another failure of mission as a whole.’ Nigeria Methodism at 180, indigenised to decolonise warns that if we ‘repress our colonial and neo-colonial histories, they will come back to haunt us all the more. The relation of mission and colonialism took different shapes in the different contexts. Nigeria Methodism at 180, indigenised to decolonise points to David Bosch’s description of the early British colonialists[7] who ventured and worked without missionary support and ‘in the nineteenth century the missionaries could rely on the support of the economic and political structures that had been established.’

Nigeria Methodism at 180, indigenised to decolonise as a means of theological and missiological lessons reminds us of the guilt burden related to colonialism[8] and the need to learn from the past. Globalisation as a new form of colonialism has the potential ‘to confuse the notion of bringing Christ to the nations with bringing Him to the nations in western garb,’ culture and theology. Nigeria Methodism at 180, indigenised to decolonise counters the church-state paradigm that ‘advanced the Western political and religious agenda across the world.’

Nigeria

Methodism at 180, indigenised to decolonise points to the belief that

evangelisation needed to precede civilization. This is based on the supremacy

of evangelization over civilization with the assertion ‘that

social change would come as a consequence of the impact of the gospel.’[9] Nigeria Methodism

at 180, indigenised to decolonise is not just a transplanted church, like a

potted plant transferred to a new culture and expected to grow and reproduce exactly

as it did in the colonial culture.[10] Nigeria Methodism at 180, indigenised to decolonise is a

testimony of a contextualized church, ‘like planting God’s seed in new

soil and allowing the seed to grow naturally adapting to the language, thought

processes, and rituals of the new culture without losing its eternal meanings, including ‘a

biblical perspective of God, Christ, the Holy Spirit, the church, humanity, time and

eternity, and salvation.’

[1] Neill, Stephen, Colonialism and Christian Missions. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966), p. 414

[2] Cooper, Michael, T, COLONIALISM, NEO-COLONIALISM AND FORGOTTEN MISSIOLOGICAL LESSONS, http://ojs.globalmissiology.org/index.php/english/article/view/105/302

[3] Bediako, Kwame, Theology and Identity: The Impact of Culture upon Christian Thought in the Second Century and Modern Africa (Oxford: Regnum Books, 1992), p. 35-55

[4] http://edinburgh2010.org/fileadmin/files/edinburgh2010/files/Resources/UBS%20Kumar%20-%20Postmodernism%20Globalisation.pdf

[5] Rieger, J., “Theology and Mission between Neocolonialism and Postcolonialism,” Mission Studies 21.2 (2004): pp. 201–227.

[6] Bosch, David, Transforming Missions: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission (Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis, 1991), pp. 303-305

[7] Bosch, Transforming Missions, pp. 303-305

[8] Sanneh, Lamin, Christian Missions and the Western Guilt Complex, Evangelical Review of Theology, 1995, 19:393-400

[9] Beaver, R. Pierce, `The Legacy of Rufus Anderson, Occasional Bulletin of Missionary Research 3: 1979, pp. 94-97.

[10] Walls, Andrew, The Missionary Movement in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission of Faith, (Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis, 1996), p. 226

Recent Comments