| A great tree has fallen. The world has lost Professor Andrew Finlay Walls, the doyen of the academic study and the founder of the contemporary field of “World Christianity.”[1] Prof Walls’ missional/academic legacy on “missiology as a vocation”[2] is evidence in his decades-long labour, lectures, giving, research, and project, ‘upending staid interpretations of Christian history by examining the role of mission and cross-cultural transmission of the Gospel in the formation of World Christianity.’[3] For Prof Walls, World Christianity is normative Christianity though often obscure by traditional Western ways of viewing church history.[4] Prof Walls’ work provides missional and theological insights, and successful counters to secular critics of “World Christianity.”[5] The term “World Christianity” according to Dana Robert was used and applied by Prof Walls to describe the realities of ‘the study of Christianity beyond the captivity of Western frameworks.’ Prof Walls’s argument was that ‘the cross-cultural diffusion of the gospel was the foundation of scholarship on Christianity as a worldwide, multicultural religion—a fact not yet appreciated by Western scholars.’[6] Professor Allan Anderson’s reference to Professor Inus Daneel’s extensive writing has constantly striven to purge for example, ‘the study of African independent churches from Western misconceptions.’[7] According to Anderson, ‘before a Westerner can comprehensively understand anything really African, it will be necessary to attempt to detach oneself from presuppositions, such as the dualism that sees everything in terms of ‘secular’ and ‘spiritual’ (or sacred).’ Anderson’s reference to Oosthuizen and Parrinder on when a Westerner is talking about ‘the supernatural world’ and the ‘suprarational and suprahistorical disposition’ of Africans, or about a ‘spiritual religion,’ then something is usually being described which is set over against the opposites: natural, rational, historical, secular, and so on.’[8] The African world-view is holistic, ‘that sense of cosmic oneness … fundamentally all things share the same nature, and the same interaction one upon another … a hierarchy of power but not of being, for all are one, all are here, all are now … No distinction can be made between sacred and secular, between natural and supernatural, for Nature, Man and the Unseen are inseparably involved in one another in a total community.’[9] Anderson criticized ‘the tendency of Western observers to filter African phenomena through their own cultural and theological grid, without penetrating the African thought world in any depth.’ Anderson quoting from the works of Dierks shows how some of the main evaluations concerning African interpretation and theology itself in Africa, suffer themselves from the Western tendency towards ‘investigating and systematizing things or experiences by means of dispassionate analytical probing.’[10] Anderson’s argument is that ‘the dualistic, rationalistic theology of Western historical churches simply did not meet the need of the African for divine involvement’ and using the words of Professor Bolaji Idowu, ‘one of the major assignments before those who seek to communicate and inculcate the Gospel in Africa is that of understanding Africa and appreciating the fact that they must learn to address Africans as Africans.’[11] The results of the lack of interdisciplinary field of World Christianity ‘were either that traditional spiritualism went underground, or that a syncretism emerged in the encounter between African and Western world views.’ Another alternative, especially in the Spirit-type churches was the discovery ‘that biblical doctrine of the Holy Spirit was not as detached and uninvolved as Western missionaries often made it out to be!’[12] Prof Walls understood that the African need for divine involvement was met in the doctrine … which becomes in Africa both contextualized and a manifestation of biblical reality.’ In essence, the Western tendency to dictate, redefine, oppose or ‘discount the emotion in religion made Western forms of Christianity unattractive to a great many Africans. The pervading Spirit in the Spirit-type independent churches gave Christianity a new vibrancy and relevance to African.’[13] Prof Walls lives on and remains one of the most important interpreters of Christianity and its missionary role in our time.[14] According to Professor Afe Adogame, ‘Prof. Andrew F. Walls was a pioneering figure, intellectual giant, and erudite scholar who contributed immensely to the “making” and “shaping” of the interdisciplinary field of World Christianity. His encyclopedic knowledge, grasp, and “thick description” of the church’s transformation from Christendom to world Christianity transcends disciplinary boundaries of religious studies, history, theology, mission studies, biblical exegesis, and runs deep into the life and DNA of the church.’[15] Historian John Dickson in his new book Bullies and Saints: An Honest Look at the Good and Evil of Christian History, shows the importance of an honest and missional approach to Christian history and biblical reality. Dickson’s work which allows us to see God’s faithfulness even when those who claim God’s name are rejecting His ways resonates with Professor Andrew Walls’ principle and approach which according to Joel Carpenter of Calvin University ‘challenged many of the basic assumptions of Western theology.’[16] |

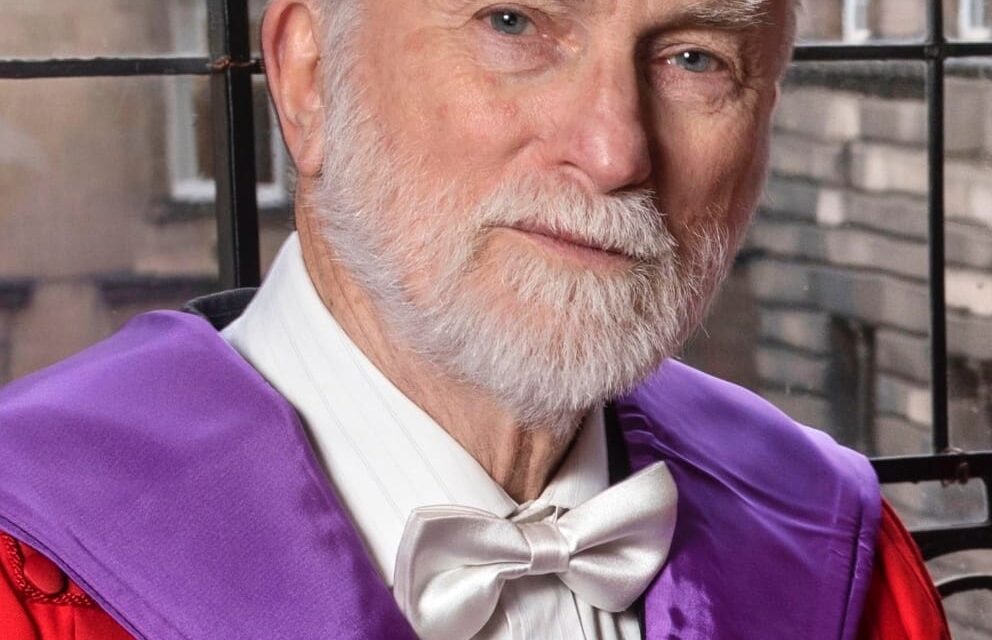

Prof Walls, Honorary Professor of World Christianity at Princeton Theological Seminary and founder of the Center for the Study of Christianity in the Non-Western World at the University of Edinburgh, lives on. He died on Thursday 12th August, 2021 at age 93 as an old man but rather than burning down the library, he has not only contributed to the establishment of libraries in many places,’ he has ‘entrusted his principles of exemplary Christian scholarship to the minds and hearts of his students in nearly every country,’ including myself as one of the stewards of these principles. Against the opinions of others scholars such as Philip Jenkins on ‘a shift of power from Western churches to those South of the equator, Walls sees instead a new polycentrism: the riches of a hundred places learning from each other. That is why he has delighted in the Centre for the Study of Christianity in the Non-Western World, which he founded at the University of Edinburgh.’ He was ‘much an African at heart as he was a global missiologist with the whole world being his parish as demonstrated by his global mileage.’

Prof Walls was a pioneering historian of Christian missions and their reception, and in many ways the architect of the field of study now known as world Christianity.[17] He was born in New Milton, England in 1928. Between 1945-51, He studied theology at Exeter College, Oxford, receiving a first-class degree in 1948. Between 1951-52, he was recognised as a Teacher of Hebrew and Ecclesiastical History and Doctrine, University of Bristol. He worked as Librarian at Tyndale House, Cambridge between 1952-57 and between 1957-62, taught at Fourah Bay College, University of Sierra Leone. Walls completed his graduate studies in the early church in 1956 under the patristics scholar Frank Leslie Cross.[18] In 1962, he moved to Nigeria and taught at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka until 1965. In 1966, he was appointed to a post in Ecclesiastical History at the University of Aberdeen. In 1970 he became the first head of the Department of Religious studies at Aberdeen. In 1986 he moved to the University of Edinburgh, becoming Director of the Centre for Study of Christianity in the Non-Western World, 1986-87.

Prof Walls was trained as a patristic scholar at the University of Oxford. On his childhood and early religious experiences, Prof Walls explained that, he came from a working-class family. Prof Walls, a historian ahead of his time said, “My mother was traditionally devout. Though I believe he prayed every day of his life, I don’t recall my father ever going to church. Like many people from that generation, he believed that the church had abandoned working people and was not standing for righteousness. The person I have realized since that was a great influence on me was my grandfather, who lived with us. He had run away to sea from Dundee at the age of twelve and had travelled the world. He eventually settled down looking after sheep in Patagonia. My earliest memories include floods of what I now realize to be very bad Spanish, but also insights into things from all over the world. He himself was a rugged old unbeliever, but the impressions remained with me for a long time. I went to Sunday school and church and in adolescent years made a commitment to Christ.”[19]

Prof Walls will be ‘remember for his deep Christian faith, expressed through a life-long attachment to Methodism, but with sympathies that extended to those of every denomination and none.’ Prof Walls was a member of Aberdeen Methodist Church for over 50 years, ‘and was active as a preacher through the North of Scotland Mission Circuit.’[20] My personal experience and encounter with Prof Walls as my External Examiner resonates with the words of Gillian Bediako. Prof Walls was very ‘deep, meticulous scholarship, combined with an equally profound evangelical spirituality and heart for mission, … read the signs of the times in what was happening to Christianity around the world and saw, before anyone else, that the heartlands of the faith were changing.’ He made me one of the emerging scholars and a church leader in the non- Western world. I remain grateful to Cliff College and the Manchester University for the honour of getting Prof Walls as my External Examiner. I agree with Kwabena Asamoah-Gyadu that it would be impossible to study World Christianity ‘from whichever perspective—theology, mission, history, pastoral care and counselling, or ecumenism—without encountering the work and influence of Andrew Walls. He has left us an impressive heritage in faith and scholarship that will remain truly global and unparalleled for generations.’ Using the words of Emma Wild-Wood, I will remember Prof Walls for his ‘historical perspicacity and his attention to primary sources are a matter of public record’ and for his enablement to ‘hear the rhythm and music of cultures that had been marginalized in the modern era and to see them as central to the Christian movement in the 21st century.’[21]

Rev Dr Stephen Skuce, my doctoral Internal Examiner, a former Director of Global Relationships, The Methodist Church in Britain, and currently the District Superintendent, the North Western District, Methodist Church in Ireland explained that Prof Walls ‘focused on the vital task of training local mission scholars and had the grace to hand over to his students who now lead nationally and internationally.’ According to Skuce, Prof Walls ‘understood the importance of hearing the story of mission from those who received as well as those who shared. Prof Walls reduced the role of the foreign missionary to one working alongside numerous other local people, and helped rewrite mission history avoiding the disproportionate focus on the foreign missionary that had been the norm for generations. We take for granted today the fruits of his pioneering work.’ Skuce’s memories of Prof Walls, ‘despite world recognition and in advancing years ‘are of Prof Walls willing to travel around Nigeria as part of a Cliff College teaching team along with the rest of us, being part of the group when he was by far the star. He lived mission as well as studying and teaching mission.’

For me, Prof Walls was an exemplar examiner and ‘teacher who made his students to see the world, themselves, and the Christian faith in a new light.’ My PhD viva with Prof Walls in 2011 changed the trajectory of my life and ministry. His examination ‘is like putting on a new pair of glasses that bring everything into focus that you have been missing or never seen before.’ He was a humble examiner. At a point during my viva, Prof Walls challenged me on a section of Nigerian Christian history that only few people may remember. Prof Walls said, “Deji, this is a very good work, but why using CAN (Christian Association of Nigeria) for the case study? Is CAN not about going to Jerusalem and collecting Christmas turkey from government…? My response to him generated another question on Church Union in Nigeria in 1966/67. Prof Walls said, “Deji, I put it to you that there was a Church Union in Nigeria. I have the Order of Service for the inauguration of the Church Union. In his humble manner, my response really took Prof Walls unprepared. I said, “Professor Walls sir, If you have any Order of Service for the inauguration of the Church Union, it was illegal as there was a court injunction to halt the programme.” In response, Prof Walls said, “Yes, you know what you are saying, though one of the Methodist leaders was behind it.” At this point, I said, “It was not Professor Bolaji Idowu, because, I believe, you are referring to him. Some lay members went to court” (we both laughed together). At the end of my successful viva and with some corrections to be made, Prof Walls gave me his complimentary card for contact on how to liaise on the interdisciplinary field of World Christianity. I remain forever grateful to my supervisor Rev Dr Phil Meadows and the management of Cliff College, Calver, for the support and love I received throughout my stays and studies (2007-2011).

Prof Walls, a giant from an age of legends is called by Christianity Today as “the most important person you don’t know.” Beyond his gentle and humble nature, the missional significance of Walls life’s work[22] is ‘known for recentering contemporary Christian history in the Southern hemisphere and, along with the late Lamin Sanneh, promoting the voices of African, Latin American, and Asian Christians.’ [23] Prof Walls was trained as a scholar of the early church and ‘this equipped him to see how the contemporary African church was asking questions that echoed the concerns of the second-century church, as described by Justin and Clement, and the conversion stories recorded in the seventh and eighth centuries by Gregory of Tours and Bede.’ Walls came to Africa in 1957 as a 29-year-old veteran of Oxford and Cambridge planning to fulfil his missionary call through teaching church history at Fourah Bay College. After five years in Sierra Leone, Walls and his family—his first wife, Doreen, and two small children—moved to Nsukka, Nigeria, where Walls headed up the religion department in a new university. He was beginning to grasp the dynamism of the African church. On one enormous wall, he and a colleague created a map of East Nigeria and endeavoured to record every last place of worship. They began to collect old church registers.[24] They found hundreds and hundreds of baptismal registers, marriage registers, discipline books, and committee minute books. Some of them went back to the 1880s. It was an African church with African executives, keeping its records with varying degrees of efficiency, according to the degree of education of the people involved But there it was: working, witnessing, worshiping, sinning, repenting. All this going on for a 70- or 80-year period.” In Nigeria, Prof Walls studied the growing churches of Africa and their history and learned of vast revival movements, of foundational preachers and evangelists, of extensive church networks with their own ideas about order and their own ways of viewing Scripture.[25] Professor Wall left Nigeria in 1966, weeks before civil war erupted. While he was gone, the library burned, and he lost the entire collection of church materials. He returned to Africa at least once annually over the next 40 years, but never again to live. Prof Walls’s life, work, and mission in Africa provide the background for understanding his unique contributions to the church and academy. The body of work that Walls has developed adumbrates a journey of humble listening and quest for empathetic understanding. He shows us a myriad of reasons why we live in a moment for the church that is filled with immense opportunity, challenges, and promises for witness and mission.[26]

On his return to United Kingdom, Prof Walls taught at the University of Aberdeen between 1966 and 1986. He became a scholar of international renown, establishing the Centre for the Study of Christianity in the Non-Western World (now known as the Centre for the Study of World Christianity), and supervising many research students who became leaders in both church and academy. The Centre was established as a library and archival resource, documenting the history of missions and the growth of non-western Christianity: the students followed, attracted by the sources. [27] According to a tribute from The University of Edinburg, School of Divinity, ‘One of his last academic duties was to offer closing reflections at the online Yale-Edinburgh meeting in June 2021. His legacy is preserved in various institutions across the globe, in a host of published papers, and above all in the person of his former students. Andrew remained a regular visitor to the Centre until the end. The University of Edinburgh bestowed on him an Honorary Doctorate of Divinity in 2018, and in the following year Andrew was delighted to see his precious Centre archives integrated into the University’s Centre for Research Collections.’ Prof Walls was an embodiment of ‘genuine, ground-breaking scholarship, just as his generosity of spirit, time, intellectual energy, theatrical gifts, appreciation for literary works, and his sense of humour is robustly contagious.’

Among the legacies of Prof Walls is the missional shift of the church in the 20th and 21st centuries, especially ‘the astonishing shift of Christianity’s centre of gravity from the Western industrialized nations to Asia, Africa, and Latin America.’ American church historian Mark Noll says that “no one has written with greater wisdom about what it means for the Western Christian religion to become the global Christian religion than Andrew Walls.” Prof Walls’s missional insights probe Christian history to gain a prophetic vision of what “Christian” really means across an extraordinary diversity of times and cultures. Prof Walls, on his return home, ‘still vividly remembers the contrast between the vibrant African church and the dwindling vitality he found at home in Scotland. Faculty meetings were desperately dull, mainly because “nobody wanted anything.” Church buildings were being turned into bars. At Aberdeen, theological students took three years of church history: early church, Reformation, and Scottish. Ten years before, Walls would have approached such a curriculum with zest. Now it seemed hopelessly inadequate.’ Beyond the English Christians idea of holiness of the 18th and 19th centuries of activism for mission and against slavery, Prof Walls had begun to see churches in Africa and Scotland as part of a bigger story. How is the faith transmitted and transformed across cultures? Through what process does the rationalistic faith of Scottish Christians become the visionary, supernaturalized life of Nigerians? Prof Walls saw the spread of the gospel not ‘as inexorable progress outward, like an inkblot,’ but ‘that time and again the real story was of ebb and flow. The loss of Christian territory happened not just on the periphery but at the heartland. Jerusalem was the first heartland until the Romans levelled it, and the Jewish church all but ceased to exist. Then came Rome, until the northern Vandals sacked it; Constantinople, until Islam overran it; northern Europe, before Enlightenment scepticism cut its heart out. At each turning point, the gospel made a great escape, crossing over into an unknown culture just before disaster struck. History suggested that Christianity lives by this pilgrim principle.’ Prof Walls’ groundbreaking research re-centering Christianity from West to South ‘capture the extraordinary richness of Andrew’s long life—a life that was devoted to Africa, the world church, to his many graduate students, and to his collaborators in his multiple scholarly enterprises in the history of missions and world Christianity.’[28] According to Professor Brian Stanley, ‘There are many of us who can testify that it was Andrew who first gave us our vision for the work of chronicling, documenting, and interpreting the transformation of Christianity from its apparent status as a European-dominated religion to a faith that now finds its most vibrant expressions in the global south and in migrant churches in the northern hemisphere.’

Prof Walls, with his vast knowledge of Christian history and mission concealed in a gentle and caring demeanour is described by Adeleye Femi as ‘the first to articulate the significance of the rapid expansion of Christianity in the non-Western world with his now widely acknowledged prophetic declaration on “the passing of the Christian Centre of gravity from the west to the south.” In the words of Prof Walls, “more than half of the world’s Christians live in Africa, Asia, Latin America or the Pacific, and that the proportion doing so grows annually.” It was through the efforts of Prof Walls (in Sierra Leone and Nigeria) that “departments of Religious Studies as we now know them in Britain were born in West Africa, the product of a plural society where religion is a massive, unignorably, fact of life,” but also affirmed that “the missionary movement is a connecting terminal between Western Christianity and Christianity in the non-Western world.” Prof Walls said, “We cannot talk about Africa without Christianity and Christianity without Africa.” Kwabena Asamoah-Gyadu explained that Prof Walls was able to hold ‘students and other listeners spellbound with his incisive and engaging sense of the place of Africa in global Christianity. We cannot be wrong in calling Prof. Walls the doyen of the academic study of “World Christianity.’

Prof Walls’ ‘numerous facts and figures of the Bible, history, and theology together in ways that you could have never imagined’ according to Sam George points to Professor Walls’ ‘ability to discern across centuries and continents in a truly polycentric global manner is unparalleled.’ The legacy of Prof Walls, according to K. C. Wendell is about ‘the Word made flesh, Christ tabernacling in every culture, ethnicity, and people group, —the African, the Indian, the Chinese Christians, or perhaps more specifically the Nigerian, the Tanzanian, the Singaporean Chinese Christians and the like—a face and a voice.

Prof Walls was not limited to the

academy. He has served as an Aberdeen City councillor, and as Chairman of the

Council for Museums and Galleries in Scotland. In 1987 he was awarded the OBE for

his public service, especially to the arts in Scotland.”[29]Prof Walls was a Professor of the

History of Mission at Liverpool Hope University, Honorary Professor at the

University of Edinburgh, Research Professor at Africa International

University’s Center for World Christianity, and Professor Emeritus at the

Akrofi-Christaller Institute of Theology, Mission and Culture. He established

the Journal of Religion in Africa in 1967. A complete listing up to 2011 is

given in W R Burrows, M R Gornik and J A McLean (eds), Understanding World

Christianity: the vision and work of Andrew F Walls, Maryknoll NY: Orbis 2011,

pp 257-277. Works since then include Crossing Cultural Frontiers: Studies in

the History of World Christianity (Maryknoll NY: Orbis 2017). He received the

Distinguished Career Award of the American Society of Church History in 2007.[30]

We

extend our prayers and heartfelt condolences to his second wife, Dr Ingrid Reneau Walls, a fellow

theological scholar, his children, and to all the family.

[1] Walls, Andrew, F. Crossing Cultural Frontiers: Studies in the History of World Christianity (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2017), pp. ix, x, 3, 4

[2] Walls, Crossing Cultural Frontiers: , p. 259-266

[3] Walls, Crossing Cultural Frontiers: , p. xi

[4] Walls, Crossing Cultural Frontiers: , p. xi

[5] Walls, Crossing Cultural Frontiers:, p.

[6] “Professor Andrew Finlay Walls: A Tribute”. Centre for the Study of World Christianity, https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2021/august/andrew-walls-world-christianity-edinburgh-yale-tributes.html

[7] Anderson, Allan, Moya: The Holy Spirit in an African Context (A Project of the Institute for Theological Research) (Pretoria: University of South Africa, 1994), p. 2

[8] Anderson, Moya: The Holy Spirit in an African Context, p. 4

[9] Anderson, Moya: The Holy Spirit in an African Context, p. 4

[10] Dierks cited in Anderson, Moya: The Holy Spirit in an African Context, p. 5

[11] Bolaji Idowu cited in Anderson, Moya: The Holy Spirit in an African Context, pp. 9, 5

[12] Anderson, Moya: The Holy Spirit in an African Context, p. 9

[13] Anderson, Moya: The Holy Spirit in an African Context, p. 9

[14] Walls, Andrew, The Missionary Movement in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission of Faith (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1996), pp. 3-15

[15] https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2021/august/andrew-walls-world-christianity-edinburgh-yale-tributes.html

[16] https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2021/august/andrew-walls-world-christianity-edinburgh-yale-tributes.html

[17] http://www.cswc.div.ed.ac.uk/2021/08/professor-andrew-finlay-walls-a-tribute/

[18] Stanley, Brian (October 2001). “Profile of Andrew Walls,” Epworth Review 28 (4): 16–26.

[19] On the Road with Christianity, A conversation with missiologist Andrew Walls by Donald A Yerxa, https://www.booksandculture.com/articles/2001/mayjun/6.18.html

[20] “Andrew F. Walls,” Aberdeen Methodist Church.

[21] https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2021/august/andrew-walls-world-christianity-edinburgh-yale-tributes.html

[22] Walls, The Missionary Movement in Christian History: pp. 43-54

[23] https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2007/february/34.87.html

[24] https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2021/august/andrew-walls-world-christianity-edinburgh-yale-tributes.html

[25] Walls, Andrew F, The Missionary Movement in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission of Faith (Maryknoll, NY; Orbis Books, 1996), pp. 79-101.

[26] https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2021/august/andrew-walls-world-christianity-edinburgh-yale-tributes.html

[27] http://www.cswc.div.ed.ac.uk/2021/08/professor-andrew-finlay-walls-a-tribute/

[28] https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2021/august/andrew-walls-world-christianity-edinburgh-yale-tributes.html

[29] https://www.ed.ac.uk/divinity/news-events/latest-news/archive/2018/honorary-grad-prof-andrew-walls

[30] https://www.ed.ac.uk/divinity/news-events/latest-news/archive/2018/honorary-grad-prof-andrew-walls

Recent Comments