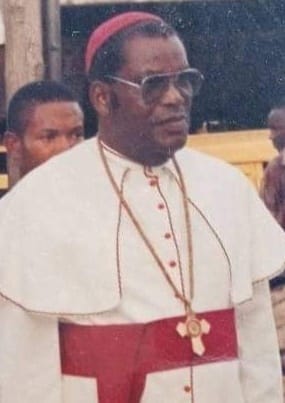

When death on Friday January 1st, 2021 came to find Archbishop Amos Abiodun Omodunbi, a former Secretary of Conference (SOC), Methodist Church Nigeria, and a retired Methodist Archbishop of Lagos, it found him alive. The transition and frontline roles of Archbishop Omodunbi echoes the Methodist understanding of authority and Church government derived from the character of Methodism as a ‘connexional’ Church. Archbishop Omodunbi promoted ‘the interdependence which properly lies at the heart of connexionalism naturally precludes both independence and autocracy as modes of church government.’[1] Archbishop Omodunbi modelled a style of episkope and episcopacy with a personal lifestyle that Methodists should not fear that the practice of episcopacy would involve the practice of a hierarchical model. Archbishop Omodunbi placed emphasis on the pastoral, teaching and missionary roles of the bishop and relational in character.

The first form of Methodist episkope was personal episkope, the ministry of oversight (both pastoral and authoritative) of one man, John Wesley. This was changed ‘after Wesley’s death, the Methodist Conference was given legal continuity by the Deed of Declaration, which Wesley has executed in 1784 to bestow upon the Legal Hundred those powers which he himself had held.’[2] Methodist experience of episkope began with the Conference and still exercises episkope over the people called Methodists. The Conference communal exercise of episkope ‘is characteristics of Methodism’s way of exercise oversight.’ The term ‘episkope’ is the Greek word for oversight’ while ‘episcopacy’ is the oversight exercised by bishops, and churches with the office of bishop within their missional structures is called ‘episcopal.’ Example of Methodism’s communal exercise of episkope watching over each other and taking counsel together about the life of the church is the Representative Session of the Conference while the Ministerial and the Lay Sessions ‘are better described as collegial.’ In Methodist ethos, personal episkope is missionally possible and exercised in a collegial and a communal context.

Nigerian Methodist episcopacy rooted in permanence is coherent in the fact of its historicity and spirituality.[3] His Pre-Eminence (Prof) Bolaji Idowu, the father, the first, and ‘the learned’ Patriarch, Methodist Church Nigeria, a pioneer in developing African Christian Theology and one of the most influential theologians in Africa in his Presidential address in 1973 and his other publications called for indigenous ministry rooted in Scripture. Beyond the idea of a ‘native episcopacy’ of self-governance, self-supporting, and self-propagation,[4] Patriarch Idowu’s vision for selfhood of the church and believe is that, the coming great church will be indigenous and episcopal in its life, mission, and order. The contemporary church (ekklesia) in Nigeria has largely lost it sense of ecclesiology and leadership. The practice of Nigerian Methodist corporate episcopacy from the heart with historic and other missional elements in the Christian tradition as lived by Archbishop Amos Abiodun Omodunbi provides a renewing legacy for us today. Episcopal oversight is essential because “a call to church membership is a call to discipleship.”

Historic and corporate episcopate as an institution is characterised by succession in office and the succession in consecration and investiture. This is missionally for ‘the general superintendence of the church and more especially of the clergy; the maintenance of unity in the one Eucharist; the ordination of men (and women) to the ministry; the safeguarding of the faith; and the administration of the church … What we uphold is the episcopate, maintained in successive generations by continuity of succession and consecration, as it has been throughout the history of the Church from the earliest times and discharging those functions which from the earliest times it has discharged.’[5] The strength of historic episcopate is in the continuity of Scripture, the rule of faith, and the Sacrament … and in the continuing stream of Christian prayer and action inspired and empowered by them, that the substance of the Church’s life resides. Legitimate succession cannot of itself guarantee the integrity of these things, but if taken in conjunction with them it enriches their witness and strengthens their power.’[6] Nigerian Methodism expresses the historical episcopate, corporately and indigenously ‘adapted in the methods of its administration to the varying needs of the nations and peoples called of God into the unity of His Church.’ In John Pobee’s estimation, the challenge which indigenous churches and African traditional religions have posed for western Christian institutions is leading to ‘a more ‘charismatic’ expectation of the episcopate’[7] especially when ‘there are many Christianities that aren’t very Christian.’

Bishop’s ministry is characterised by two aspects – a permanent, institutional aspect and a renewing historical aspect hence, bishop’s role has varied in different periods. However, Archbishop Abiodun Amos Omodunbi’s life and transition rekindles the two characteristic aspects of the collegial and corporate episcopate of New Testament times in contrast to synodical government or the ‘so called ‘monarchical’ bishop of the second and third centuries.’ According to His Eminence Samuel Chukwuemeka Kanu Uche, ‘Archbishop Omodunbi as a good manager of human and financial resources was a colossus, an ecclesiastical encyclopaedia, a committed and devoted leader who moved Nigerian Methodism and episcopacy forward.’ Augustine, Bishop of Hippo (354-430) on his office as bishop aptly points some unique virtues of episcopacy which resonates with Archbishop Omodunbi’s teaching and episcopal ministry. In his entire teaching, sport and episcopal ministries and engagements, Archbishop Omodunbi rebuked agitators, comforted the faint-hearted, took care of the weak and the strong, confuted enemies, took heed of snares, taught the uneducated and educated, woken the sluggish, held back the quarrelsome, put the conceited in their place, appeased the militant, gave help to the poor and rich, liberated the oppressed, encouraged the good, endured the evil and betrayals and he loved all.

Church history from the first century through today is ‘very clear that Chrstians are prone to believe all sorts of things that are not in line with what God has revealed in the Bible.’ Archbishop Omodunbi’s pattern of episcopacy from the heart beyond the pre-Nicene model, or the type of bishop-administrator found in medieval and modern times is with a clear line of demarcation between the things of Caesar and the things of God. Archbishop Omodunbi’s episcopacy from the heart is in contrast to the radical change of episcope to lordship, a privileged group at the ‘very heart of the res publica’ in the Constantine period.[8] Archbishop Omodunbi was not only a bishop in name but in deed especially in relation to the fourfold missional tasks of the bishop in shepherding, consecration, ordination and confirmation. Archbishop Omodunbi in fulfilling the role and function of episcopacy in the guardianship of the unity of the church lived missionally the office of ecclesiastical unity and communion.

For Archbishop Omodunbi, corporate episcopal ministry is about change, lordship to episcope, a missional function not for fame. For him, episcopal ministry is for witness not for wealth. Archbishop Omodunbi as ‘a quintessential Methodist episcopal frontliner’ lived a missional expression of ‘the corporate episcopate’ the orderly transmission of ordinations by bishops, in intended visible continuity with the mission of the apostles shaped by the Methodist Church’s understanding of the nature and mission of the Church (its ecclesiology) and to its corporate connexional polity.[9] Episcopacy from heart attests to Archbishop Omodunbi’s theology of keeping the goal of missional leadership and indigenous norms exemplified Bolaji Idowu theology and true to the Wesleyan Scriptural holiness. Archbishop Omodunbi in his episcopal office understood itinerancy in general and itinerant, general superintendency not as monarchical ‘lords,’ ‘but a recovery of the New Testament pattern of leadership; that of Christ and the apostles. In the model of the first bishops of Methodism, Coke and Asbury (though disapproved being called bishops by Wesley) and shaped by Eastern Orthodoxy, Archbishop Omodunbi operated corporate ‘episcopacies to effect a distinctive recovery of apostolic leadership — ministry as missional, evangelistic, sent, appointed/appointive – “a royal priesthood …’

Archbishop Omodunbi as a model of episcopacy from the heart points to how the Methodist Church understood the ministry of a bishop, that is episkope and episcopacy in relation to corporate oversight exercise within a particular area of responsibility and connexionally in the wider church is both individual and collegial.[10] This is supported by ‘a leading role, alongside presbyters, deacons and lay people, in church government. They have responsibility for the transmission and safeguarding of the apostolic faith, for providing for the administering of the sacraments, and for leadership in the Church’s mission.’ Archbishop Omodunbi as a Nigerian Methodist episcopal frontliner suggests what sort of bishops[11] and the question of episcopacy in the contexts of indigenous mission as well as unity. For Archbishop Omodunbi, ‘a Methodist matter as much as an ecumenical one. … as a Methodist matter, episcopacy is … a public and social matter as it relates to the potential enhancement of the contribution that the Methodist Church makes to public life, as part of its mission as a church.’ Archbishop Omodunbi’s Methodist episcopacy from the heart is about personal humility in ‘shared oversight.’ This points to the fact that ‘any exercise of personal (lay or ordained) or corporate expressions of oversight cannot be self-sufficient or independent of each other but must be intrinsically linked with the other expressions. Since Wesley’s death, oversight in Methodism has been corporate in the first instance and then secondarily focused in particular individuals and groups (lay and ordained). Therefore at the heart of oversight in the Methodist Connexion is the Conference which in turn authorises people and groups to embody and share in its oversight in the rest of the Connexion. Methodist episcopacy as accountable episcopate points to a shared episkope (personal oversight), bearing in mind that missional oversight is inescapably relational and anything in contrast can be harmful. The legacy of Archbishop Omodunbi reminds us that ‘there is no episkopos, overseer ‘in insolation, but only in relation to others in connexion.’ In his ministry within Methodist church that spanned almost 60 years, Archbishop Omodunbi made an outstanding contribution to the strong foundation of Nigerian Methodist episcopacy. He also contributed immensely to theological training and education at Immanuel College of Theology, Ibadan, Methodist Theological Institute, Sagamu, Methodist Theological Institute, Umuahia, and Hassan Odukale Methodist Theological Institute, Zonkwa.

There have been many fitting tributes sketching Archbishop Omodunbi’s outstanding contribution to the Methodism in Nigeria. His mentoring and ‘compassionate articulation of the Church’s teaching communicated the inherent dignity of human life and the human person to a broad audience.’ Archbishop Omodunbi without ever being condescending or dismissive, he inspired confidence in the truths of Methodist faith and his teaching profession brought perceptive insight, with a no nonsense presentation of what was at stake. His Eminence Sunday Ola Makinde, a prelate emeritus, Methodist Church Nigeria and one of the students of Archbishop Omodunbi described Archbishop Omodunbi as a great man, a lover of education. Prelate Makinde said, “Archbishop Omodunbi was a teacher of teacher, pastor of pastors. He was a leader who was extraordinarily contented. His students were made bishops the same day with him. He was contented teaching and imparting Wesleyan and New Testament concept of church leadership in school while his mates were made bishop. Nigerian Methodism needs contented leaders like him. His ministry was productive. He raised and produced a prelate, archbishops, bishops, presbyter, and priests of high integrity. I am proud to be one of his students. I am proud to be his brother. I am very proud to be one of his products.”

Rt Rev Dr Kolawole Solanke, a former Bishop of Remo, Sagamu, in his foreword to ‘Fruits of Obedience: The Biography of the Most Rev Amos Abiodun Omodunbi authored by Prince Adegoke Adedire Arimoro, described Archbishop Omodunbi as ‘ecclesiastically ecumenical in his relationship with other denominations and ministers of God.’[12] According to Bishop Solanke, Archbishop Omodunbi was ‘a friend of his students, a dependable and honest teacher, a creative administrator, a father Pastor, a candid counsellor, a pedantic pedagogue, and a resourceful agile sportsman … a great defender of the Community of Faith – the Church and a gallant soldier of Christ … a giant among clear level-headed pilgrims and a self-disciplinarian who is also a disciplinarian.’ Archbishop Omodunbi ‘has trained or made many “Priests unto God” and so has got “Children” and “Grandchildren” who are Archbishops, Bishops, Presbyters, Venerable, Governors, Teacher, Sportsmen, and Administrators in the Church and the society.’ A former Prelate, Methodist Church Nigeria, His Eminence Dr Sunday Ola Makinde and Archbishop Ayo Ladigbolu are among the notable students of Archbishop Omodunbi.

Archbishop Omodunbi never sought a high media profile as a quintessential Methodist episcopal frontliner despite taking a keen interest in the press. Archbishop Omodunbi was illustrative of several truths about Methodist bishops that often go unacknowledged or under-appreciated. First of all, Archbishop Omodunbi was an accomplished theologian and despite his erudition, Archbishop Omodunbi had a strong common touch. As a local bishop, he emphasized being close to his people. He was a passionate but a quite disciple of Patriarch Idowu, the father of Nigeria Methodist episcopacy. Patriarch Idowu was elected on 4th October, 1972, consecrated on Sunday 20th Jan, 1973 at Tinubu and retired at the attainment of age 70 on 28th Sept 1984. Archbishop Omodunbi was never political but always made his presence felt among the people, and most especially with his ministers, standing with them and defending them when necessary.

Archbishop Omodunbi, the ‘Asiwaju Onigbagbo of Osu,’ was born on 24th December, 1933 to a devout Methodist family of Pa Jacob Omoleiyo and Victoria Aina Omodunbi of Agunja quarters, Osu, the Headquarters, Atakumosa West Local, Government, Osun State. In 1939, Archbishop Omodunbi started his elementary education at Methodist Primary School, Oke Oja, Osu. After a break of few months due to sickness, Archbishop Omodunbi followed his uncle, Mr Isaac Fakolade, a teacher at Methodist Primary School, Ijeda-Ijesa where he completed his A, B, C elementary education in 1941. Archbishop Omodunbi moved with his uncle on transfer to Methodist Primary School, Otan-Ile, where he completed infant 2 in 1941. He finally moved again to Methodist Primary School, Itagunmodi-Ijesa in 1942 where he completed his Standard 1 Education. He later returned to Methodist Primary School, Oke Oja, Osu, to complete his elementary education Standard 1 to 6, up till 1947.

In 1947, Archbishop Omodunbi sat for entrance examination to Ilesa Grammar School, and Wesley College, Elekuro, Ibadan. In 1952, he was admitted as one of the pioneer students at the Methodist Laymen Training Institute, Sagamu, under the leadership of Rev Olu Adegbola and completed the training in 1953. Archbishop Omodunbi served as an Evangelist at Methodist Church, Igbogbo then under Tinubu circuit in 1954. He served at Methodist Church, Agbeni, Ibadan between 1955-1956. In 1956, Archbishop Omodunbi was admitted into Wesley College, Divinity Department, and in 1958 left Wesley College with other 9 students to join their Anglican counterpart at Melville Hall, Kudeti, Ibadan, to begin as pioneer students of the Immanuel College of Theology. He completed his studies in 1959 and in the same year enrolled for Diploma in Theology examination of the University of London as an external candidate. Archbishop Omodunbi passed with outstanding records in the same year, 1959. In 1960, while serving as the pioneer minister, Methodist Church, Sapele, area covering the present Edo and Delta State, Archbishop Omodunbi enrolled for Inter-Bachelor of Divinity Examination of the University of London and passed with flying colours.

Rev R T Williamson, Archbishop Omodunbi’s lecturer in New Testament Studies at Immanuel College recommended him for the award of Scholarship by the World Council of Churches (WCC)’ hence Archbishop Omodunbi was able to ‘complete the Bachelor of Divinity degree at the University of London.’ He married his beloved wife Mrs Florence Adedunni Omodunbi at Methodist Church, Oke Oja, Osu, in June 1961 before he left the shores of Nigeria for London on September 8, 1961. Archbishop Omodunbi completed the degree programme with flying colours in 1963. He returned to Nigeria ‘with three awards of excellence as the best student in New Testament, New Testament Greek and Christian Ethics.’ He was ordained as a full Minister at Hoare’s Memorial Methodist Church, Yaba in August 1963 while serving as a lecturer at Methodist Theological Institute, Sagamu, and Methodist Teachers Training College, Sagamu. In December 1963, he was posted to Methodist Church, Itesi, Abeokuta. In 1965, ‘due to dearth of graduate teachers for the newly established Methodist High School, Ibadan, he was invited to teach in the school. In 1971, ‘due to dearth of Theological lecturers at Immanuel College, Ibadan, he was transferred to this College. He rose to the position of the Vice-Principal within the period of one and half years.’ He was later admitted for Masters of Philosophy (Biblical Studies) at the University of Ife (now OAU). He graduated from Ife with brilliant success in 1975. In 1976, corporate episcopacy was introduced into Methodist Church Nigeria by Patriarch Professor Bolaji Idowu. Archbishop Omodunbi returned to Immanuel College after his Masters degree and in 1977 he was elevated to the post of the substantive principal and became the first College alumnus and ‘the youngest person to head the College.’ Archbishop Omodunbi took over form Bishop Solaru who was elected as a Methodist Bishop in 1977. Archbishop Bola Gbonigi served as the Vice-principal to Archbishop Omodunbi.

Patriarch Idowu, above all odds was able to recognised Archbishop Omodunbi’s brilliance and transparency and he was elected as a Bishop and the first Deputy Secretary of Conference at the famous 1984 Methodist Church Nigeria Conference held at Jesus College, Otukpo. Sir Folorunso Ogunjuyigbe explained that Archbshop Omodunbi’s consecration as Bishop took place in Lagos with the investiture of His Pre-Eminence Sunday Mbang (and later Prelate), consecration of Archbishop Ayo Ladigbolu and His Eminence Sunday Ola Makinde (as bishops) respectively. Archbishop Omodunbi was the first minister from Osu to be elected as bishop. At Archbishop Omodunbi’s thanksgiving service at Methodist Church, Oke Omi, Osu in early 1985, His Eminence Mbang delivered the sermon while His Eminence Makinde, (as chaplain to His Eminence Mbang then) interpreted the sermon in Yoruba.

The Methodist crisis was part of the reason for the creation of the position of the Deputy Secretary of Conference. It is important to note that Archbishop Poromon emerged as the Secretary of Conference in 1976. Archbishop Rogers Uwadi who was elected as a Bishop and as the Secretary of Conference in 1981 and took over from Archbishop Poromon who finished his term in 1980. Archbishop Uwadi ‘rose from the rank of a presbyter to become Secretary of Conference and a bishop at the same time,’ and he was consecrated on 29th November, 1981. Archbishop Uwadi’s assumption of office at the peak of the Methodist crisis remains triumph of faith over fear and fighting. Archbishop Omodunbi described Archbishop Uwadi as ‘a young man endowed with a lot of dynamism, divine energy and vision. He is very able competent and resourceful. He immediately on taking over reorganised the headquarters. A man of sterling quality, he contributed in no small measure to the enviable height Methodist Church Nigeria has reached today. His record keeping is immaculate. His articulation is unparalleled. His humour is superb. His mastery of conference meeting is delightful. His knowledge of the constitution is marvellous. At both national and international level, he is a worthy representative of Methodist Church Nigeria.’ In 1986, Archbishop Omodunbi was elected as the substantive Secretary of Conference at the Methodist annual Conference held at Kaduna. Archbishop Omodunbi in his humble nature conferred respect, legitimacy and honour on His Eminence Mbang as his ‘Oga’ (master).

During the Methodist crisis which started in 1974, under the patriarchy of His Pre-Eminence Sunday Mbang, there was a meeting of the Methodist two sides – Patriarchal and Presidential (Fusion Committee) held on 14th July 1989 at Methodist Church, Ijoku, Sagamu. Archbishop Omodunbi conducted the devotional service – Methodist Assembly, attended by about a thousand people. Preaching from the two passages read – Neh 2:17-20 and 1 Cor 3:1-15, Archbishop Omodunbi pointed out the two pictures that emerged from the two passages, namely, ‘challenge and response,’ and ‘the divided church of God torn apart because of party spirit built around personalities…’ Archbishop Omodunbi said, “We are here for peace, for reconciliation and nothing else. We are not here to argue or justify ourselves. We have all sinned and left Methodist Church Nigeria in disgrace. God says it is time to remove our disgrace. The work of reconciliation, restoration and reconstruction is not easy because there would always be Samballats and Tobias around us but Methodist Church Nigeria should take courage in the realisation of the fact that the God of Israel is with us and He will be with us as He was with Nehemiah.”[13] Archbishop Omodunbi’s four reasons why we should come together are very helpful for the repositioning of Methodist Church Nigeria today.[14] We need to come together, ‘… because of our wretched and disgraceful position in which people were asking us which side of the Methodist Church we belong to, another was in unity lies our strength, thirdly, because of the bitter experience of the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) of the government, fourthly, because Christ is the Great Reconciler and He has given the work of reconciliation to us … To make Methodist Church Nigeria ONE is a task that must be done,’ Archbishop Omodunbi appealed to all Methodists to be open minded as history was being created at that time. On Wesley Day, May 24, 1990, at the Reunification service at the Hoare’s Memorial Methodist Church, Yaba, Lagos, Archbishop Omodunbi read the ‘Declaration of purpose.’

In 1992, Archbishop Omodunbi with His Eminence Mbang, Archbishop Dimoji and Sir Ogunjuyigbe represented Methodist Church Nigeria at the United Methodist Conference held in Louisville, Kentucky, USA. In 1996, after two years as Deputy Secretary of Conference and 10 years of eventful service as the Secretary of Conference, Archbishop Omodunbi at the Methodist Conference held at Ikot-Ekpene, Akwa-Ibom State, was translated to the Diocese of Ifaki as the Diocesan Bishop. His successor, Archbishop Michael Stephen described Archbishop Omodunbi as a mentor and role model with ‘an understanding of what Methodism is all about.’ According to him, “Archbishop Omodunbi was somebody who knew that position of responsibility in Methodist Church Nigeria is not to seek for naked power. Archbishop Omodunbi used his positions and powers to work with others to further and promote the vision and mission of Methodism in Nigeria. He was not into power seeking and grabbing. He was a person who sought assistances from whoever, either from his junior or senior colleagues with the belief that he had not all the answers. As SOC, he consulted me regularly and always took to my advice which were later helpful to me as his successor. Archbishop Omodunbi exposed me to the church administration even when I was a teacher and later as a principal at Methodist Theological Institute, Sagamu.” On Archbishop Omodunbi’s close working relationship with him and other ministers, Archbishop Stephen bemoans lack of trust among ministers today. According to him, ‘unlike when we used to spend the night in each others houses, such is no longer the case because the church is falling for the madness of Methodist episcopacy. Leadership today is about bishops using other ministers to serve them perpetually as sycophants, thinking that they only have the answers. Among the lessons to learn from Archbishop Omodunbi is to make progress by encouraging and furthering fellowship among ministers. Archbishop Omodunbi’s simple lifestyle and delegation of duty warns us that leadership is not about preaching at every occasion. It is about making ways for others to ensure that they are learning just as Archbishop Omodunbi did.”

Archbishop Omodunbi’s first major regret was in 1996. His driver, employed less than one year, bolted away with a large sum of church money, N200, 000.00 kept in the car at a Conference meeting at Ikot Ekpene. God really used His Eminence Dr Sunday Mbang to rekindled confidence and his trust in Archbishop Omodunbi’s integrity. After some security search, the driver was later caught and recounted his misdeeds. Sir Ogunjuyigbe said “it was a very sad event ending glorious twelve years of meritorious service of Baba as SOC.”

On September 1st, 1997 at Ifaki, Archbishop lost his beloved wife Mrs Florence Adedunni Omodunbi when she was 59 years old while Archbishop Omodunbi was 64. The transition of Arcbishop Omodunbi’s wife, Florence Adedunni, at a time when she was planning to retire from her Nursing profession in order to take care of her husband was big blow and Archbishop Omodunbi’s second tragic regret in his career. In 1999, God provided a virtuous woman that understood and appreciated Archbishop Omodunbi’s circumstances. Archbishop Omodunbi married Mrs Mary Olayinka Omodunbi on June 12, 1999 and she lovingly took care of baba till his transition.

In 1998 at the Methodist Biennial Conference at Ode-Aye, Igbobini, Archbishop Omodunbi was elevated to the post of Archbishop and translated to the Archdiocese of Lagos until his retirement in November, 2003. Archbishop Omodunbi resumed as Archbishop of Lagos operating in a small office within the premises of Hoare’s Methodist Cathedral, Yaba. Sir Dele Taiwo, who served as Lagos diocesan treasurer, explained that Archbishop Omodunbi without complaining lived with his wife ‘in a 3 bedroom apartment donated by a member of Olorunda Local Church without complaining until a member of Olowogbowo Cathedral, Lagos, Sir Aremo Pearce released a bungalow at Adeniyi Jones, Ikeja for the use of Archdiocese as Archdiocese House for a period of time. It was during his tenure that we started the planning of a permanent Archbishop’s House at Tabontabon, Agege. He computerised the Archbishop’s office. He brought in his wealth of experience as a former Secretary of Conference by asking the Treasurers Bro G O Fashoto and myself to set up a better accounting framework for the office. His tenure in Lagos prepared the previous 3 years accounts which were equally audited.’

When it was obvious there was no church policy on retirement house for bishops, some of his members in Lagos including Dame Femi Sonola, Sir Demola Aladekomo, Sir Remi Omotoso, Sir Adebola Olufon and others came together to build a house for Archbishop Omodunbi at Lekki, Lagos. As a lively and people person, he later moved to Ojodu until his transition on January 1st, 2021. Archbishop Michael Ogo, a retired Methodist archbishop of Enugu who served as Deputy Secretary with Archbishop Omodunbi explained that Archbishop Omodunbi, a detribalised leader ‘represented a gone generation of leaders with value for human life and family.’ Gab Awopeju described Archbishop Omodunbi as ‘one of the most thorough Secretaries of Conference, Methodist Church Nigeria when he was in charge of the administration of the Conference Headquarters. Brilliant. Meticulous. Composed. Cool-headed. Clear-headed. Level-headed. Humane. Urbane. Godly. A teacher of teachers in the Word. Exemplary leader and the quintessential episcopal frontliner. Blessed are they who remained steadfast in faith and constant in friendship.’ Bishop Joel Akinola described Archbishop Omodunbi as a ‘great soldier of Christ. You allowed us to go for further studies and you were instrumental to Conference decision of five steps for graduate priests of which I am a beneficiary. You equally supported our ministry at Osu Circuit many years ago.’ In the words of Archbishop Ayo Ladigbolu, ‘OGA Abiodun Omodunbi took his call very seriously and gave himself wholly to serving the Lord with all his gifts and talents. Many may not know that he was a Greek scholar and a New Testament teacher of note. He gave Immanuel College of Theology Ibadan its WAR CRY in Greek. OGA loved sports and excelled as a football coach and soccer enthusiast. His time as Secretary of Conference saw the development of sporting activities in all Methodist schools nationwide. He was a Minister who submitted totally to the directions of Conference. He went wherever he was “needed most” until his retirement. He bore his aches, pains, and losses with great fortitude, and remained a role model to many throughout his life time. Archbishop Omodunbi was my personal friend, brother, and loving boss.’

Archbishop Omodunbi did not sell his soul for ambition. He did not compromise his ministerial calling for human favour or connections. My close contact with Archbishop Omodunbi was made possible by Very Rev Emmanuel Okoosi, a former presbyter of my local church, Methodist Church, Oke-Oja, Osu. Very Okoosi was privy to my invitation by a major denomination to train me as their minister. At the time Very Rev Okoosi introduced me to Archbishop Omodunbi, there was a vacancy at Wesley House, Lagos, for the position of Editor/Conference Editor. Archbishop Omodunbi bluntly told me, ‘go and apply with others and try your luck. There is no partiality in the process.’ After my successful interview and resumption, there was an opportunity to give a panel van to my department. To my disappointment, Archbishop Omodunbi without mincing words told me ‘so ra eee (be careful), don’t spoil my work, are you here because of a car?’ When Archbishop Ladigbolu tried to intervene, Archbishop Omodunbi’s response was that, ‘what will people say, knowing that Deji is from my home town?”

Archbishop Omodunbi was a strong advocate for peace and reconciliation, having witnessed

first-hand the terrible divisions and heartbreak endured by people during the

crisis. Archbishop Omodunbi’s life and transition warns against secularisation

of the episcopacy in view of our awareness of its origins. To avoid this

dangerous and misleading development that gave rise to the autocratic

authoritarianism of some traditions, a missional understanding of Methodist

episcopacy requires ‘that it be both individual and communal.’[15] Archbishop

Omodunbi as a grassroot minister ‘also understood the joys and struggles of his

brother priests and bishops who often had to minister in the midst of great

challenge, grief and community unrest.’ He was always quick to offer a calm and

reassuring word in times of difficulty. Archbishop Omodunbi brought a

pastoral and informed voice to a wide range of issues, particularly welfare of

ministers, prompt payment of salary especially to the supernumeraries, widows,

clergy education, catechetic and pastoral renewal. Archbishop Omodunbi had a

keen insight into the reality of people’s lives and he never failed to bring

his extensive pastoral experience to bear on discussions at the Bishops’

Council, Synods and Conference tables. As a teacher, he nurtured young people

in the faith, sports, ‘and encouraged them to make the most of their gifts and

educational opportunities; this remained his message to the thousands of young

people on whom he conferred the sacrament of confirmation over many years.’ The

summary is that, Archbishop Omodunbi passed through the Nigerian Methodist episcopacy

and the Nigerian Methodist episcopacy passed through him. Worthy is the Lamb!

[1] The British Methodist Conference Agenda, 1999, p. 207

[2] The British Methodist Conference 2002 Special Report – Episkope and Episcopacy

[3] Methodist Church Nigeria: The Asaba Retreat Document, February 1-3, 1974, Matters Relating to the Life of the Church and Faith and Order, pp. 1-13

[4] Page, Jesse, The Black Bishop: Samuel Adjai Crowther (London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co, ND), p. 185

[5] Conversations between The Church of England and The Methodist Church: An Interim Statement, SPCK and Epworth, 1958), pp. 16-27, 23

[6] Conversations between The Church of England and The Methodist Church: p, 19

[7] Pobee, John quoted in Thomas, Philip, ‘The Historic Episcopate, Locally Adapted’: An Element of Anglican tradition,’ in An Anglican Evangelical Journals for Theology and Mission (ANVIL), vol 15, No 2:1998, pp 94-97

[8] Schmemann, Alexander, Historical Road of Eastern Orthodoxy (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1977), pp. 62- 69

[9] Richey, Rusell, E, Introduction in Richey, Rusell, Campbell Dennis, Lawrence, William (eds), Connectionalism: Ecclesiology, Mission and Identity (vol 1) United Methodism and American Culture (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1997), p. 9

[10] Episcopal Ministry: The Report of the Archbishops’ Group on the Episcopate 1990 (London: Church House, 1990), pp. 13-78, 190-195

[11] Ware, Kallistos, ‘Patterns of Episcopacy in the Early Church and Today: An Orthodox View, in Moore, Peter (ed), Bishops: But What Kind? Reflection on Episcopacy (London: SPCK, 1982), pp. 1-24

[12] Arimoro, Adegoke Adedire, Fruits of Obedience: The Biography of the Most Rev Amos Abiodun Omodunbi (

[13] Familusi, Michael, Methodism in Nigeria (Lagos: Methodist Publishing, 2012), pp.195-196

[14] Okegbile, Deji, Missional Leadership for Repositioning Nigerian Methodism (Lagos: Alet Inspirationz, 2019), pp. 33-61

[15] Wilson, Kenneth B, ‘Episcopacy in Theology and Practice,’ in Epworth Review, Volume Five, Number two, May 1978, p. 99

Recent Comments